As Yachtsnet specialises in sailing yachts, we will not discuss powerboats. For a sailing yacht, you have a number of choices: |

|

Keep the boat at home: There are small sailing yachts designed to be towed on a trailer, and launched when required. Although at first glance this might seem to be a good choice for smaller boats - up to a maximum of perhaps 25-26 ft. there are few people that actually do this, for good reason. In comparison with launching a small powerboat from a trailer, launching and rigging a sailing yacht is very time-consuming, as you have to put up the mast and rig sails. Many people with “trailable” boats in fact only launch them in spring and retrieve them in autumn, leaving them on a mooring or marina berth through the summer. The trailer is a way to keep them at home in the winter, at no cost, and to be convenient for working on maintenance. |

| |

Most trailer-sailers either have relatively little ballast, or use water ballast tanks to aid stability, the water ballast being drained when the boat is brought ashore to tow, to reduce towing weight. This generally reduces their performance compared to most other sailing boats. |

| |

There are a few trailable sailing boats that are designed to be dual-purpose “power-sailers”, with a sailing rig plus a powerful engine to give planing powerboat performance. These, on the whole, are neither very good sailing boats or very good powerboats, yet for some people are a useful compromise, particularly for lake or very sheltered water use. |

|

|

Moorings: When we talk of moorings we mean boats tied to buoys in a harbour. You will need a means of getting to the boat, usually via a dinghy kept ashore, or in some places there are “water taxi” services that will take you to your moored boat. Some yacht clubs offer a similar “club launch” service for club members, but all these services have one snag - if you get back to your mooring late in the evening, the club or water taxi service may have stopped running. |

| |

Moorings themselves come in several flavours - the three main types being deepwater moorings, drying moorings, and trot moorings. |

| |

Deepwater moorings are not necessarily in especially deep water - the phrase simple means that the mooring position will always have enough tidal height to keep the boat floating. In popular locations deepwater moorings are highly sought after, and in many harbours there is a substantial waiting list to get one - sometimes ten years or more. So do not think you can just buy a 35 foot yacht and turn up in Dartmouth or Salcombe, and ask the harbourmaster for a yearly mooring. |

| |

|

| |

Drying moorings will let the boat settle down onto the bottom at low water, and can thus only be used by sailing yachts that can “take the ground” - usually those with bilge keels or drop keels. Drying moorings are almost always cheaper than deepwater moorings, and are usually easier to obtain, although in popular areas there can still be a waiting list. |

| |

|

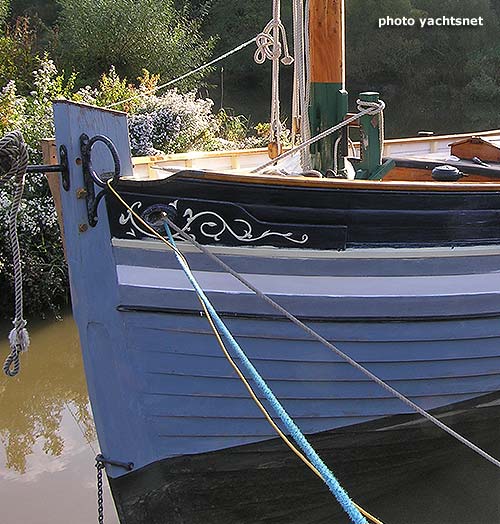

Drying moorings are found in the upper end of most estuaries: they restrict the times you can use the boat |

|

| |

Most harbours used by yachts have a harbour authority, which allocates and maintains their own moorings, and collects daily harbour dues from visiting yachts. In many places, there are also privately owned moorings, which can sometimes be sublet. |

| |

All the above moorings allow each boat to swing around to face the wind, and as a result the moorings have to be spaced reasonably far apart. Trot moorings are an alternative way of mooring, which allows more yachts to fit in a given area of seabed. Boats are moored bow and stern to a series of buoys (or sometimes steel or wooden posts) so they cannot swing in a circle. |

| |

|

Whatever your type of mooring, you need to give serious consideration to where you will keep a dinghy, unless there is a reliable water taxi or club launch service. An inflatable dinghy can be deflated and carried by car, or carried inflated on a car roof for short journeys, but most people prefer to keep a dinghy somewhere ashore, often on a rack in a yacht or sailing club compound. |

|

|

Pontoon or marina berths: when a yacht’s “berth” is referred to it usually means a marina berth, where the boat is moored alongside a pontoon walkway, that leads you to the shore, and usually a bar/restaurant, showers, car parking etc. For most people these are by far the most convenient places to keep a sailing yacht, but inevitably they are always more expensive than moorings, even although the fact that boats do not move once berthed means that a lot of boats can be fitted into a small space. Many marinas are near full, and some have waiting lists for berths, though currently if you are prepared to pay their rates, most will find you a space fairly quickly. |

| |

|

Some marinas have sections in shallow water where boats dry out at low tide - these berths are usually cheaper than their deep water berths where yachts can stay afloat at all states of the tide.

Many marinas are also behind lock gates - meaning that to get to sea you have to pass through a sea-lock, and in some places the lock can only be used at near high water time.. |

|

| |

In quite a few places (always ones where there is pressure to pack more boats in) pontoons are moored in mid-river or mid-harbour. These are usually substantially cheaper than marina berths. |

|

|

| |

Pontoon berths with no walk-ashore access.

As with moorings, you need a dinghy or water taxi/club launch service to get to your boat. |

|

|

|

The final option for keeping a sailing yacht is to “dry sail” her. This means that the boat stays ashore in a boatyard, until you phone them and tell them you want her in the water on a given day. You arrive on the day, and your boat is afloat on a convenient pontoon mooring, ready for you to step aboard. The cost is often similar to a pontoon berth - the snag is that you may be out of luck getting launched if you wait to phone the yard till the morning of the first day of a bank holiday weekend. |

| |

Dry-sailing is popular with racing yachts, as the hull stays clean. It is also used extensively for small powerboats, often stored in racks as in the photo at left |

|

|

Types of yacht |

|

Trailer-sailers are more popular in the USA than in the UK, perhaps because American cars are usually bigger and more powerful than British ones. Probably the most popular trailer-sailers in the UK are Cornish Shrimpers and Crabbers, small gaff-rigged yachts with a lifting centreboard, and the French Beneteau 210/211/217 21 ft mini-yachts. About the biggest practical trailer-sailers are the US-built MacGregors and Hunter Legends, and a number of Polish built lift-keel yachts such as the Sportina range. The attraction of trailer-sailers is obvious - keep it in the drive at home, take it to different places each holiday, no permanent mooring fees, just launch site charges and a few days visitors mooring costs. If you are considering buying a trailer-sailer, however, do not underestimate the work and time involved in rigging and derigging it each time you launch. |

| |

|

| |

Most trailer-sailers are shallow keeled, or have centreboards or lifting keels (see below). Although this 30 ft fin-keeled racing yacht is towable behind a large 4x4, it is not in any sense a trailer-sailer, as it needs a boatyard crane or Travelift to launch. |

|

|

|

Centreboard yachts are relatively rare, except in the smaller sizes. The centreboard is a hinged lifting keel, which can either be heavy, and part of the yacht’s ballast, or simply a relatively lightweight keel to reduce leeway. In order that the centreboard takes up minimal cabin space, the centreboard (sometimes called a centreplate) is often mainly external. Most centreboard yachts can use drying moorings, though those with external keel stubs may lean over substantially when aground. Jeanneau and Beneteau build various models of small centreboard yachts, all with external keels. Kirie in France used to build ‘Feeling’ centreboard yachts up to about 44 ft. Currently the main UK builder of centreboard yachts is Cornish Crabbers - a 22 ft Crabber is shown in the photo above, and a Beneteau 211 with external drop keel in the photo below. |

| |

|

| |

Amongst the larger centreboard yachts are the Southerlys, built from the 1980s to early 2013, when the company went into administration - early Southerlys were as small as 28 ft, whilst the range in later years extended to 54 ft. Below - a 1990s Southerly 115 |

| |

|

|

Lift keel yachts. The phrase “lift keel” is sometimes used to refer to yachts with hinged centreboards, but also more precisely to yachts whose entire keel slides up vertically, similarly to a daggerboard in a sailing dinghy. |

| |

Until their demise in 2009 Parker Yachts built a series of quite fast cruising yachts with hydraulically raised ballasted keels. |

|

|

|

Twin bilge keel yachts (often just called bilge keel yachts, or bilge-keelers) are primarily a British phenomenon, in response to the large number of harbours with drying moorings. The French have nearly as many drying harbours, but historically they seemed to prefer lift-keel or centreboard yachts. Some bilge-keel yachts have shallow keels and hence very poor windward performance, though others can perform almost as well as fin-keel yachts. The photo below shows two different bilge-keel yachts, a very traditional Macwester with shallow keels, and a more modern British Hunter with deep efficient twin keels. |

| |

|

| |

Bilge keel yachts can sit upright on their twin keels at low tide, and also happily sit ashore in the winter on their keels, without the need for any further support. In sizes up to about 30 feet, bilge keel yachts are common in the secondhand market, but above this size they become rarer. Very few bilge keel yachts are now built - the market preference having changed to larger fin-keeled yachts. |

| |

|

Bilge keel yachts probably evolved from the bilge plates fitted to some traditional long keeled yachts, to allow them to dry out upright. This photo shows a Barbican 33 long-keeler, with bilge keels fitted, making her a triple-keeler. |

|

| |

Although this 22 ft bilge-keeled Newbridge Venturer sits on a trailer, getting her on an off and correctly aligned on the trailer is not easy |

|

|

| |

|

Very few bilge keel yachts are now built, possibly because by the time a sailor can afford to buy a brand new yacht, they can afford a deep water mooring or marina berth. The last production builder of larger bilge-keel yachts was Moodys, who until the early 2000s offered bilge keels on yachts up to 36 ft, such as the Moody 36 shown at left in a brochure photo.

The tens of thousands of older and smaller bilge keel yachts still around do however

offer an economical way into cruiser sailing for many people. |

|

| |

Fin keel yachts have a single fin keel of iron or lead, with a separate rudder blade. Currently most production sailing yachts are of this type. A reasonably deep single keel gives good windward performance, at the price of needing a deep water mooring or berth. Ashore, fin keel yachts need to be supported in cradles, or with props. |

| |

|

| |

A typical modern fin-keeled yacht - a 41 ft Beneteau - such yachts are usually built with a choice of deep or shallower draught fin keels. The charter yacht market has helped create the trend towards such yachts, big charter companies such as Sunsail and The Moorings ordering large batches of yachts each year. Volume production thus drives prices down. |

| |

Fin keel yachts usually now have a single fin keel of iron or lead, with a separate rudder blade. Currently most production sailing yachts are of this type. A reasonably deep single keel gives good windward performance, at the price of needing a deep water mooring or berth. Ashore, fin keel yachts need to be supported in cradles, or with props.

There are a number of variants of the fin keel - the most common being bulbed keels, where a fatter bulb of lead or iron is at the lowest point, to increase stability. |

|

|

| |

|

A winged keel is designed to give good sailing performance with less draught than a fin keel - there are many variations in the shapes and sizes of the wings |

|

| |

Many new production cruising yachts are now being sold with racing-derived "torpedo" keels, which are very efficient as keels, but possibly also good at catching floating debris or ropes. |

|

|

| |

|

One final keel type is rare - the tandem keel, another variation on a bulbed keel designed to allow shallower draught whilst retaining performance. Bavaria and Etap are amongst the builders offering tandem keels as option on some models of yacht |

|

| |

Most keels are made of cast iron: though lead is in almost all respects a better material it is much more expensive. Keels can either be external and bolted on to the hull (the most common type nowadays), or encapsulated, where the hull moulding includes a hollow glassfibre keel moulding that is filled with iron or lead ballast. |

| |

|

Most fin keeled yachts can, with care, be dried out leaning against a harbour wall at low tide, to scrub the bottom or look at the propeller or rudder. The longer the base of the keel, the easier and safer this is. |

|

|

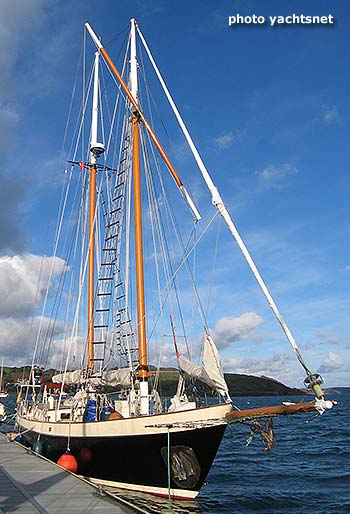

Long keel yachts are now rarely built, though a few niche market builders do still produce yachts with long keels. Technically a long keel is one that runs underwater almost the whole length of the hull, but the term is nowadays often used to refer to what is really a cutaway long keel, with the forward keel edge set back from the bow. |

| |

A true long keel yacht - a this being a Northsea 127, a modern reworking of the Colin Archer Norwegian sailing rescue boat hullform. Hulls such as this can be called long keel or full keel. |

|

|

| |

Vancouvers, built in various sizes from 27 to 38 ft, are also long-keel yachts, though they have the keel cut away at the forefoot and stern - technically they should be called long keels with a cutaway bow |

|

|

| |

|

A Rustler 31 - most people will call this a long-keeled yacht, even though the keel is substantially shorter than the hull.

Almost all long-keel yachts handle poorly in reverse, though they have many other advantages in terms of seaworthiness and steadier handling than yachts with fin keels. |

|

|

Catamarans and trimarans are multi-hulled yachts, and unlike monohulls, are not normally ballasted. There is a wide range of types, from ultra-high performance boats, to relatively sedate cruising boats. Many people like multihulls for their lack of heel - unlike monohull yachts which heel significantly as the wind increases. Critics point out that a catamaran or trimaran CAN be capsized, and once capsized will remain afloat but inverted. In practice capsizing a cruising multihull is an exceptionally rare occurrence. Multihull enthusiasts retort that monohulls can sink - but that too is incredibly rare in practice. |

| |

Modern cruising catamarans such as this 38 ft French-built Lagoon offer massive cockpit and deck space and good performance under sail, particularly offwind. |

|

The interior has a spacious deck saloon with panoramic windows, and berths in the twin hulls |

|

|

Modern trimarans tend to have accommodation ony in the centre hull, and have much less interior space than the catamarans with the whole width of the deck for accommodation. Most current trimaran designs are built for speed rtaher than interior space. |

|

|

| |

One real snag with multihulls is that many marinas charge them extra for berthing, as their wide beam takes up more space than a monohull of equivalent length. A number of trimarans, including the Danish-built Dragonflys, get round this by having outer floats which fold in to the sides of the main hull, reducing the beam to much the same as that of many monohulls. Trimarans tend nowdays to be built more for performance than for interior space. |

Construction materials |

|

GRP - glass reinforced plastic, sometimes called FRP or fibreglass is by far the most common material used now for yachts, for good reason. It is easy to form into any shape required, reasonably cheap, reasonably strong, and fairly long-lasting with minimal maintenance required. It is fairly easily repaired, and although the material does have disadvantages, its virtues generally outweigh them. GRP hulls are made of structural layers of woven and matted glass fibres set in polyester resins, with an outer cosmetic layer of a special resin called gelcoat, giving the surface smoothness and shine. |

| |

When GRP yachts were first built in the 1950s and 1960s, the material was promoted as being maintenance-free, which turned out not to be quite the case, though it is still probably the one of the lowest maintenance materials of any used for yacht hulls. The one major snag of GRP hulls is that they can suffer from what is called "osmosis" - a tendency to absorb water and suffer blisters on the surface. This is usually primarily a cosmetic defect, but in bad cases it can have an affect on structural strength. Our web page on osmosis explains this in more detail. |

| |

|

A 35 year old Nicholson GRP yacht that thanks to a quality build, and careful maintenance by her long-term owner, is still in immaculate condition. The original hull gelcoat is still glossy, and there was no sign of osmosis on the underwater hull. |

|

| |

|

Certain colours of gelcoat, darker blues, greens and reds in particular, fade badly when exposed to the sun. Add in a scratch or two, and failure to polish regularly, and you have this look on a hull just 12 years old.

It is however just a cosmetic defect - some minor scratch repairs and agood polish would dramatically improve the look, though the buyer of this yacht chose to have the hull painted.

Because of the tendency of dark gelcoats to fade, some builders including Beneteau now make all hulls white, and if the buyer wants a blue boat - it gets spray painted.

Some yacht buyers are paranoid about not wanting a GRP hull painted, thinking it must have been done to cover up major damage, but usually it is simply a means of smartening up and older and dull hull. |

|

| |

|

| |

Paint has been the finish of quality yachts for many, many years, and even now almost every billionaire's superyacht is painted from new.... |

|

Wood is the oldest material used for yachts, and few new yachts are now built in timber, though many are still sailing. As a traditional wooden boat is infinitely repairable, it has a potentially endless life, though probably the oldest small wooden boat still actively sailing is the oyster smack "Boadicea", built in 1808. There are quite a few 100 year old or more yachts still in regular use, and many thousands of 50-75 year old yachts. The quality of the timber is key to longevity, and quality wood is expensive. Whilst wooden boats inevitably need more maintenance than many other materials, a quality wooden yacht in good condition does not need that much more work to keep it up in good order. The real work comes once a wooden boat is allowed to deteriorate. |

| |

The two main traditional wooden build techniques are carvel and clinker construction - carvel having planks laid edge to edge, and sealed with caulking, and clinker planks laid with overlapping edges. |

| |

Carvel construction gives a smooth hull finish. Traditionally the seams between planks were caulked with oakum (tarred hemp fibre) and white lead, before the hull was painted, but there are many more modern variations including seams filled with glued in wooden splines. |

|

Clinker planking overlaps, the planks traditionally held together with copper rivets: the construction method gives a strong but slightly flexible hull. As with carvel construction, there are modern glued variations. |

|

Although relatively rare nowadays, there are tens of thousands of plywood boats in existence, the best of them being built in epoxy-jointed and coated ply, as in this yacht. The nature of ply sheets makes chined hull forms the easiest to build, as in this 'Naja' design.

A few yachts were built in cold-moulded ply - instead of ready-made flat sheets of plywood being used, many individual layers of thin veneers are laid up over a mould and glued together, giving a very strong, stiff curved hull.

|

|

|

|

Steel yachts are popular with long-distance voyagers - the primary reason being that a steel hull will survive (perhaps badly dented but still floating) damage that would destroy a GRP or wooden hull. Also, steel can be repaired anywhere there is a local welder. The problem with steel is that owning a steel yacht required constant vigilance to combat rust - treating any rust patches immediately they appear. It is rare to find steel yacht below 32 ft in length, though a few are around. |

| |

|

It is rare to find steel yacht below 32 ft in length, though a few are around, as it is difficult to build a light enough hull in smaller sizes. The larger the yacht, the more attractive steel becomes.

For thsi resaon steel yachts tend not to be the choice of first time buyers, unless looking for a substantial boat as a liveaboard.

|

|

|

Aluminium is one of the finest materials for yacht consruction: it is strong, stiff, and light - but it is an expensive material to build a yacht hull from, so apart from quite a number of "superyachts", aluminium boats are rare. Aluminium yachts do have some specialised maintenance requirements to avoid corrosion, but overall it is a superb material.

|

The only mass production builder of smaller yachts in aluminium is the French Ovni company, who produce a range of hard-chine centreboard yachts almost instantly identifiable by their unpainted grey metal hull sides. They are very versatile yachts, many being cruised long distances. |

|

|

Ferrocement yachts - in the 1960s and 1970s there was surge in the construction of ferrocement boats - because the raw materials were cheap. Many were amateur built, and many amateur built ferro boats were very badly built. A good one, whether amateur or yard-built, is however very strong, no heavier than a similar sized steel or GRP boat, and has minimal maintenance.

Because of the large number of badly built ferro yachts around, most insurers will not deal with any ferroceent yacht, though there are a couple of specialist insurers who will cover them.

Most ferro yachts are relatively heavy long-keelers although this is not universal - the photo at right shows a ferrocement Hartley 39 with a fairly fast cruiser-racer hull form, the design being of similar weight whether built in wood, GRP or ferro. |

|

Ferrocement yachts are always cheaper than equivalent boats in most other materials, due to the poor reputation of the material - which for a good example is totally unfounded. Beware the bad ones though! |

|

Build quality |

| |

Just as a Ferrari or Rolls Royce will be built differently to a Ford or Renault, there is a huge difference in build quality between mass production yachts and custom and semi-custom built yachts. You can buy two or three new GRP production yachts, from builders such as Bavaria, Jeanneau, Beneteau and several others, for the price of one new Swedish Hallberg-Rassy or Nordship, or an American Island Packet, of the same length. |

| |

The mass-market boat will have an interior built of computer-cut veneered ply or even in places MDF, with a small amount of solid hardwood trim. There will be visible screws holding panels together, and much of the wiring and plumbing, plus items such as pumps, engines and tanks will have been fitted to the hull before the rest of the interior was assembled on top, making later modification and repair more difficult - though rarely impossible. If a mass-production yacht has teak decks, it will be a thin cosmetic layer glued on, with a finite life before it needs repair or replacement. Unlike a cheap car, however, the boat itself will have a relatively long life - in fact we do not really know how long - as most built-down-to-a-price yachts from the 1970s and 1980s are still sailing around. Although current mass-production GRP yachts are built with thinner glassfibre shells than 1970s/80s boats, the designers now mostly use higher specification materials and more sophisticated build techniques. |

| |

The expensive “quality” yacht will probably have a more strongly built hull, but almost all of the higher price will be due to less automation in the factory, and much more hand workmanship, with more solid hardwoods and beautifully detailed joinery. Often systems will be installed after the majority of the build is finished, forcing thought as to ease of access for maintenance. The boat will almost certainly have teak decks, made of thicker planks than the cosmetic skin on cheaper boats. Because less of the build is automated, the potential for teething trouble with a new yacht may actually be greater than with a mass-production boat - but the commissioning seller should take a lot of trouble though sea-trials and “snagging” to fix these before handover. Most builders of “quality” yachts will allow buyers to specify a degree of customisation to the interior. |

| |

For the buyer of a secondhand yacht, the price differential remains - the “quality” yacht will always command a higher price than the “production” boat of a similar size. As boats age, you often find that the interior joinery of a quality built yacht survives years of wear and tear much better than the cheaper equivalent.

On deck, however, there is one big difference - the cost of replacing teak decking. With a “cheap” boat - if there is ever such a thing - with luck there will be very little external woodwork to maintain, and if there are glued-on panels of thin decorative teak they can be replaced either with new thin teak, or with one of the synthetic substitutes at not too horrendous a cost. Often, however, a “quality” yacht will have a “proper” teak deck - individual shaped thicker teak planks screwed down with hundreds of small screws, the screwhead holes plugged with teak plugs, and the planking seams caulked. Once this sort of traditional teak decking reaches the end of it’s life (often because of over-aggressive cleaning) a like-for-like replacement can be eyewateringly expensive. |